By Rudi Anna

Two tiny particles collide at speeds unimaginable.

They fuse, making energy deep within a star-core. In the speck of an instant, the energy’s light bolts out through super-heated layers to the outer star until this tiny charged ball, called a photon, shoots forth, along with infinite others, from its home world—somewhere in the galaxy Andromeda.

Shooting along streams of seriously stretched space, the photon begins a journey of 22 million light years. It will never once brake its speed.

Not until it gets to Earth.

Finishing a ride lasting longer than every human empire in history combined, the photon bounces seamlessly off two glasses— magnifying lenses. These lenses are housed inside Carolyn DeCristofano’s telescope in Plympton, Massachusetts on a cool October night with a crisp northern wind.

DeCristofano’s eye, pressed firmly around the telescope’s eyepiece, receives the photon. It graces her pupil. Born millions of years ago, it’s among the most ancient artifacts she’ll ever encounter.

This observed and absorbed light becomes an electro-chemical reaction in her brain, and the light makes her think about it.

A gift. From light years away. And on a clear night, there are thousands of them.

A boisterous, bright-eyed 45-year-old science educator with a penchant for sci-fi and Greek philosophy, DeCristofano relishes these starry-night forays. She said they symbolize the ultimate bonding experience. “These celestial lights constantly raining down provide the most intimate of connections. Starlight links me to the universe. It binds me to all of humanity. It lets me discover myself.”

Indeed, the stars above, the phases of the moon, perhaps all visible celestial bodies, make up the few things all of human civilization, from Boston to Beijing, from present day to the Trojan War, have looked upon at some point.

We’ve all seen them. We all share them.

But DeCristofano worries.

For almost 80 percent of Americans living in highly populated areas, most starlight from across the cosmos splashes down prematurely, never to play onto a curious, searching eye. With that gaze, the light will never mingle. For that gaze, the light does not exist.

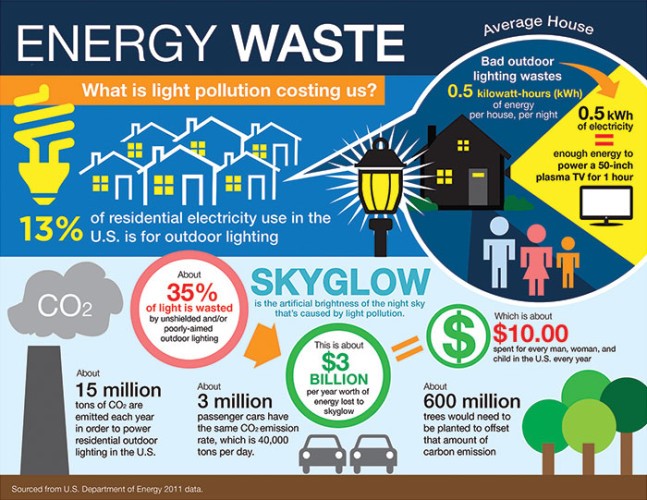

Instead, infinite starry photons wind up fizzling out in an artificial haze of over-lit cities and towns. This haze is called skyglow.

DeCristofano thinks skyglow is an unnecessary mess, separating us from the wider universe. She calls it wasteful of energy and disruptive, and she wants to clean it up.

We all know about air and water pollution, but what about light? Can this be a pollutant?

The inappropriate or excessive use of artificial light—known as light pollution—is an untended side effect of industrial civilization. It’s light going where nobody wants it or needs it to.

Its sources include a building’s exterior and interior light, advertising, commercial properties, offices, factories and streetlights. A range of studies from the American Medical Association to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service show light pollution is linked to serious health and environmental consequences for humans, wildlife and the planet.

Concern over the effects of light pollution is on the rise, and a growing number of scientists, homeowners, environmental groups and civic leaders are acting to restore the natural night.

In 2001, two years after moving to Plympton, Carolyn DeCristofano and her husband, Barry, would find themselves leading the charge to change town ordinances to control commercial and municipal outdoor lighting policy.

“Barry and I first came down here, and I think for the first time, I became aware of what he meant when he said he wanted to live somewhere with a good night sky,” said Carolyn.

She and Barry looked at several homes with a real estate agent in the summer of 2001. Every time, Barry would ask if he and his wife could come back to see the house at night—midnight. He wanted to see how dark the sky got. Most agents were taken aback by such requests.

“Yeah. You got a lot of weird looks for that,” said Carolyn, “So we had to explain that astronomy’s his first love and all that.”

Carolyn and Barry first met in Connecticut in 1982 when she was 15 and Barry was 22 years old. Carolyn’s parents surprised her sister with new car for her 18th birthday. Her sister brought along her boyfriend who brought along one of his good friends: Barry.

“There was this guy in the corner, not saying much, but I definitely noticed him,” said Carolyn.

When Carolyn’s sister married the same boyfriend five years later and had their first child, Carolyn and Barry became the godparents, separately. “We weren’t dating yet.”

In the summer of 1987, Barry helped Carolyn’s family with major renovations on their ranch house. It was an immense undertaking, with a roof being removed and replaced, and a second story added on.

“I was down there every weekend helping for months,” said Barry. “Then at night, [Carolyn’s] family would leave, just to get away from the place, but Carolyn stayed behind, so I stuck around too.”

They found they had a lot in common. Nights that summer were spent with the two young adults laying on their backs, looking up at the universe. By the time construction on the house finished, a special connection had sparked between them.

Their paths would stray for the next year, but they wouldn’t be divided for long. Barry started working at the Museum of Science in Boston, and Carolyn soon followed suit.

Then came the engagement and marriage. They bought a house in Franklin, Massachusetts. Life was good, and it was about to get a little better.

A mother of a friend at the museum was moving out of her home. She’d had 8-inch Newtonian reflector telescope locked away in storage for years and knew Barry was into recreational astronomy.

“It was this beautiful telescope she could have sold for a lot of money, but she gave it to me,” said Barry. “She knew I would share it.”

Barry and Carolyn picked up their new telescope in Middleboro. Having traveled there at night, they could tell this was a town with dark skies and a quiet temperament. They saw a house for sale. On a whim, they checked it out. They never bought the property, but the idea got them thinking.

Just before 2002, the neighboring town of Halifax opened a Walmart over former farmland. A commuter rail extension along the South Shore was announced. Despite their reasons for relocating, the DeCristofanos realized that elements of suburbia would inevitably have to play a part in their lives.

But then they noticed something else unwanted creeping up around them from seemingly all sides, and it was most noticeable on clear nights. Barry started to point out the sky glow.

“It was like a veil was being put up. And actively started looking for a new home,” said Carolyn.

Twenty-two houses later, they settled on new digs.

In large part to its natural night sky, the DeCristofanos moved to the rustic community of Plympton where the town motto is “Keep Plympton Secret.”

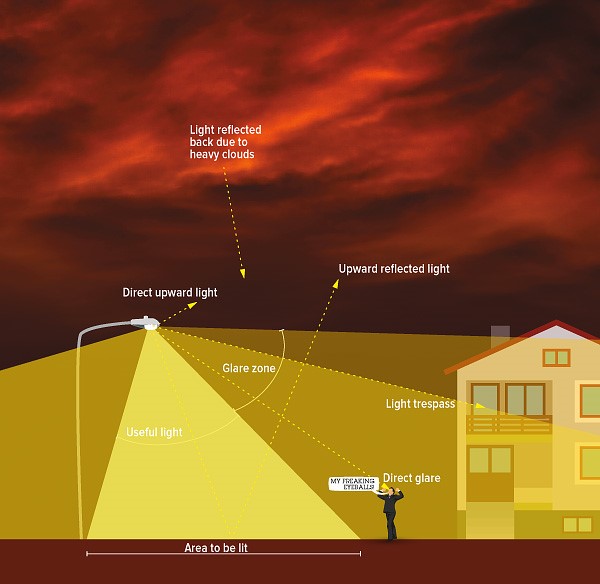

The types of light pollution

The AMA report listed three of light pollution’s most prevalent consequences:

Light glare: light emitted by a fixture that causes visual discomfort or reduced visibility. Can be dangerous especially on the road for an aging population.

Light trespass: light emitted by a fixture that causes visual discomfort or reduced visibility

Sky glow: scattered light in the atmosphere, caused by light directed upward or sideways from fixtures, reducing one’s ability to view the natural night sky

The 2016 groundbreaking World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness found 80 percent of the world’s population live under skyglow. In the U.S. and Europe, 99 percent of the public doesn’t experience a natural night.

A secret town trying to step out of the spotlight

Carolyn DeCristofano raised the issue to the town planning board members about increased light pollution, seeing the dark sky and valuing it. She noted the planning board was ‘benign’ to her ideas, and plans to change legislation were underway in early spring, 2001.

To begin, Carolyn DeCristofano and planning board members looked at what was already working. They knew that the nearby town of Plymouth already had ordinances implemented. “The idea was to borrow what was working for [Plymouth] and make tweaks along the way,” said Pat Ashton,a planning board member at the time.

Robert Smith, a realty consultant and next door neighbor to the DeCristofanos and lifelong Plympton resident, became a frequent visitor to their backyard observatory while pieces of the outdoor lighting proposal were written. Smith shared much in common with Barry and Carolyn.

Their conversations around the telescope lasted for hours. Topics ranged from dwarf planets to rampant sexism in constellation symbolism. A little scotch would fall, and Smith might join the DeCristofanos for a night of stargazing. In little time, a bond forged under the stars.

“We became close. They mentioned work they were doing to put some controls on the street lights. I felt like getting involved,” said Smith. “When you start looking up and really paying attention to the beauty out there, you become more sensitive about losing it.”

Smith ended up helping with the community bylaw’s first draft.

The DeCristofanos and other supports like Smith and members of the South Shore Astronomy Society, looked toward the upcoming hearing. They felt confident about passage.

It ended up starting a heated debate. “This got lumped in people’s minds as just another regulation, another control,” said Carolyn.

Legislation proponents felt the blow back. For many Plympton lifers, lighting control was another sign that, socially, their town was changing, and people who didn’t grow up here wanted laws that constrained a way of life people were used to.

The DeCristofanos were considered by some as outsiders trying to reach where they shouldn’t, according to Jack O’Leary who had sat on the planning board with Carolyn. O’Leary was an engineer whose previous work on outdoor lighting projects provided him insight into the technical requirements related to light glare and light trespass prevention. He’d also lived in Plympton for over ten years, which gave him some leverage.

“People hear the word ordinance, and they start thinking 1984 and Big Brother. It was across the board. Young and old were really skeptical,” said O’Leary. “They felt Carolyn had some sort of agenda to shackle the town.”

Trying to endure in a contentious climate, Carolyn started looking for alternate routes to make her point clear.

“I tried to say, ‘Look, if you don’t want things to change, you need to change the law,’” said Carolyn as part of the hearing’s closing statements. But prevailing thought, for the moment, the DeCristofanos said, was if it hasn’t changed yet, it’ll never change.

“We were just at the front of the ills of people moving in. We moved into a farmer town, and we’re part of turning it into a commuter town,” said Barry.

Seeing the electric harbingers of development in Halifax, the DeCristofanos understood what happens to towns that don’t protect their resources, and the commercial and residential development was coming. It was just a matter of time.

“But people made a big stink. They thought we were taking away their Christmas lights and that burglars would rob their house,” said Barry.

The DeCristofanos lost their first bid to pass the light pollution bylaw proposals. In Plympton, a bylaw that fails in hearing cannot be brought up two years in a row, so the DeCristofanos had to wait two years before they could try again.

They figured the best way to combat the resistance was to come against it with plenty of research, which introduced them to other individuals already doing their homework on light pollution. Looking at the stars is one thing, but they had to find other reasons why maintaining a night sky was in everyone’s best interest.

“The trick was to find a way to make the reasons for protecting the night sky support reasons why people light it,” said Carolyn.

Form following function: energy efficiency through better lighting design

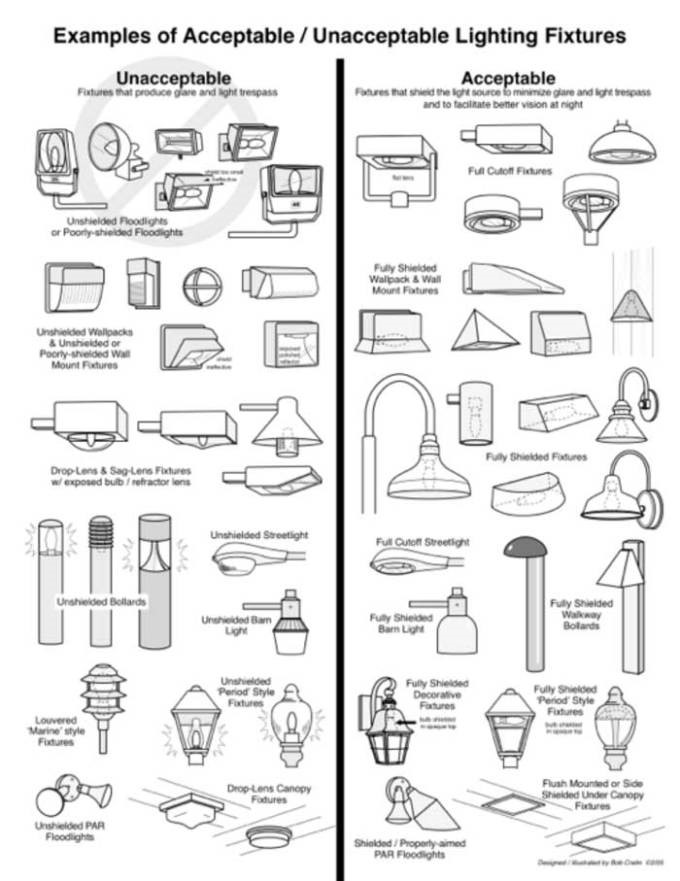

Boston-based astronomer Kelly Beatty thinks one of the reasons so much light gets wasted is because of bad design. Beatty serves on the Board of Directors at the International Dark-Sky Association, considered the leading organization combating light pollution worldwide.

“The fact is that much outdoor lighting used at night is inefficient, overly bright, poorly targeted, improperly shielded, and, in many cases, completely unnecessary,” explained Beatty at the Sky & Telescope magazine offices where he also works as a senior editor.

On unshielded light fixtures, nearly a third of the light output is thrown upward, spilling into the sky. In the United States, this results in over $2.2 billion in annual waste, according to the IDA.

“Rather than focusing fixtures completely on objects and areas people need to see,” said Beatty, “much of the light spills upward. It benefits no one.”

If poorly planned, when light is added to the environment, it has the potential to disrupt a habitat, just like running a bulldozer over the land. Hundreds of studies of artificial light’s damaging effects on migratory birds, sea turtles and salmon runs can attest to that.

Pull together the long list of damaging effects of excess lighting and it feels like a thousand-paper-cut death.

But good news can often come with modern times and updated technology.

“LED technology gives engineers unprecedented control of lighting output,” said Glen Heinmiller, a lighting architect at LAM Partners in North Cambridge which heads up several major outdoor lighting projects around the world. “In bigger cities, where street lighting resolutions are far more complex, planners and engineers must work together to make a system work for everybody.”

A new state-of-the-art wireless control system in Cambridge, Mass., a city that started testing LED conversion lights in 2010, will enable adjustment to the brightness of each of the almost 7,000 lights being replaced. Once the control system is complete, most LED streetlights will produce only 70 percent of their current brightness. Fixtures will also dim after 10 p.m., a time of less traffic, cutting light emissions further.

Beatty thinks the innovative work happening in Cambridge will serve as a gold standard in concept design for lighting policy. “I think a lot of cities still on the fence will look at what they’re doing here and try to do the same thing.” Beatty said. “People are really excited about this plan.”

Security vs. the perception of security

Plympton is a town with a population of 900. Crime isn’t a top concern or priority for most of its residents. Nonetheless, the Barry and Carolyn knew it was on people’s minds when they brought up lighting regulation and security, and it became another point of contention.

The DeCristofanos said they had to convince naysayers that controlled lighting was also secure lighting. That meant they had more research to do. Luckily, there was plenty.

“Show me a paper that says lights cut crime,” said Mario Motta, the North Shore cardiologist who recently co-wrote an American Medical Association study on the health effects of excessive outdoor lighting. Motta claims there is no study that successfully makes a correlation between lighting and safety.

He cites several studies, highlighting one conducted in 2000 called the Chicago Alley Lighting Project. The city wanted to boost the number of lights in alleyways. The intuition was more lights equaled reduced crime.

In a controlled experiment, half of the alleys were lit, and half were left dark. Both experimental and control areas were similar with respect to demographics, socio-economic status and crime.

“They found that crime actually went up in the lit alleys and down in the dark ones. Light brings attention to it. It also creates hard shadows that are easy to hide in,” said Motta.

Heinmiller thinks “overlighting for safety is a rampant problem. It’s a kneejerk reaction based on the incorrect premise that more light is going to make you safer.”

When making placement and design decisions for fixtures, Heinmiller said most lighting designers look first at safety issues. Can a passerby see properly? Is there light glare? Is the light’s color too jarring?

For security, “it’s more about a sense of security. Light can’t protect you, but it sure can make you feel safer,” said Heinmiller.

It’s worth a second try

Back in Plympton, almost two years after the first attempt, the DeCristofanos, Smith and O’Leary were at their second hearing for lighting control. They put all their research into two thick packets and a tight PowerPoint presentation. They had research on crime rates, how shielding lights reduces not only sky glow, but blocks out disabling glare.

It made driving safer, especially for many in Plympton’s rapidly aging population.

An Executive Office of Elder Affairs report projected Plympton to experience a 157 percent increase in it 65 and over population. Per the AMA report, “the older people get, the slower it takes for their retinas to make adjustments to lighting contrasts.”

An increase in older eyes behind the wheel means poorly designed lighting could become a driving hazard. Do nothing, proponents warned, and the town’s glare problem had potential to get lethal. “That point hit home for some,” said O’Leary.

In addition, warmer LED lighting entered the marketplace. It cut energy costs, lasted longer and didn’t disrupt animal behavior and native ecosystems. For every stakeholder and opinion they came across, the DeCristofanos wanted to know what the reservations were and make sure they were clearly addressed in the bylaws.

“We didn’t want any unintended consequences,” said Carolyn.

Closing their case was an appeal to town pride. Showing composite-satellite imagery of the Earth at night to chamber of people in town hall, Barry kept zooming in the photo until he was hovering over New England. The image shows some pixilation, but the point is clear, there is a tiny dark patch on the map for nearly a hundred square miles, right where they were standing. It brought home the idea that the sky was a natural resource, almost untouched by the smear of street light, something of value for Plymptonians to protect.

The second time around, and with an overwhelming majority, the citizens of Plympton adopted the new ordinance. It became mandatory for town and commercial buildings to put shielding on street lights and building lights to prevent glare and trespass. The DeCristofanos helped save Plympton’s night sky.

Since 2003, the energy costs have lowered significantly in Plympton, per town planners.

Finding the right balance

As other towns and cities across the nation deal with outdoor lighting policy, each one will grapple with its own complexities lighting priorities. These are modern times. A little light will always be in demand. But the dark is important too.

“It’s important to try and eliminate the unintended consequences,” said Heinmiller, who has worked as a consultant to city planners trying to fine tune their own city’s lighting proposal. Heinmiller warns against bylaws that might be over-restrictive. “A lot of ordinances aren’t well thought out. They’re made by planners who don’t know much about electric light.”

Towns like Plymouth, Plympton and Melrose adopted new ordinances and made sure they sought approval by experts the whole way. Cities like Cambridge are in the final stages of passing lighting laws that would set the global trend for adaptive outdoor lighting systems.

What happens by losing the stars?

When not working with students and teachers on the latest STEM learning assignment, Carolyn DeCristofano writes science books for children. When she writes, her goal is to get young readers some understandable information about big scientific ideas, but also to put kids in a conversational mood about science and math. Her books include titles like, A Black Hole is Not a Hole, or The Big Bang: The Spark that Became Spectacular!

“I want to get kids curious, and then focus that curiosity,” said Carolyn. “I want them to fall in love with a fulfilling process of wonderment.”

Most troubling for her, is what is lost in the absence of a night sky brimming with starlight. “I think we close doors. The night sky’s been a natural resource since humans started looking up. It’s one of our best-known sources for inspiration and education. For kids who grow up without it, I think we might be cutting them off from asking bigger questions.”

Carolyn’s editors remind her of this on every revision. While writing her most recent book, Carolyn’s editor had to remind her that when she describes the Milky Way galaxy as ‘a bright band of light streaking across the sky,’ she might have to pull back a little and first explain what the Milky Way is.

The reason gives her pause: a clear majority of American children will grow up never seeing the Milky Way.

“I just had to accept that some of what I was writing about would not be something readers could be expected to connect with first-hand, which I worry could cause frustration,” said Carolyn. She’s concerned reading about the night sky and not having access to it will be one more reason why someone will turn away from, rather than toward, nature, astronomy, and science. “The impact of that on our society is already tremendous. Without a science-literate public, we have major issues, right?”

A key problem is that light pollution, by its very nature, obscures its own severity, making it hard to spread awareness because people don’t understand what they’re missing. The worse it gets, the more you forget there’s something missing in the first place.

‘A lack of stars thwarts children from falling in love with wonder,” said Carolyn, taking in the interstellar panorama.

Finally, she aims her gaze on Andromeda, named for the mythological princess made prisoner and bound to a rock until Perseus set her free. “There’s nothing you can lament more than that. It’s worth fighting for.”