Kepler Telescope data show that something is blocking the light coming from a star named KIC-846.

What that something is has scientists beyond baffled.

By Rudi Anna

12/8/2016

EARTH– Most scientists tend to labor in labs outside of the public eye. This might be because the general populace doesn’t have the interest or requisite understanding to pay attention to the work.

Usually, it takes an event like moon landings or massive black holes to capture imaginations and gather enough interest to push the science into the spotlight.

One of those events just occurred. Cue the media.

News stories have been gushing about KIC-846, a distant star with peculiar behavior located almost 1,400 light years away in the constellation Cygnus. The star’s conduct has been so bizarre that a team of astronomical researchers at Yale University, led by Tabetha Boyajian, have published their findings about it.

The publication offers many possible explanations. However, it’s their final and most indirect theory for the star’s strangeness that has people buzzing.

They think it could possibly, could maybe, could potentially, be aliens.

KIC-846 is one of the more than 140,000 stars and planets observed by NASA’s four-year Kepler orbiting telescope mission.

Things Start Getting Weird

Astronomers like Bovajian are especially interested in the dimming of a star’s brightness. KIC-846, at first glance, seems like a typical main-sequence star, like 90 percent of the others in the universe. But further observation has shown a host of peculiarities in the star’s brightness readings

“We’d never seen anything like this star,” Boyajian said. “It was really weird. We thought it might be bad data or movement on Kepler’s spacecraft, but everything checked out.”

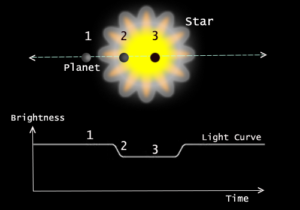

Many factors can cause star light diminutions. Bovajian and her team specialize in determining when they’re caused by an orbiting planet.

“If a star has planets, and one or more of them orbits the star at just the right angle so it passes directly in front of the star as seen from Earth, a portion of the starlight is dimmed,” said Bovajian. “It’s like a solar eclipse, but seen from light years away.” These planet crossings are called ‘transits’.

The Kepler Telescope’s Big Job

Most transits ever found are by Kepler. It measures the brightness of stars with such incredible precision, it can detect the transits of planets as small as Earth—even if that reduces the starlight by only a tiny fraction of a percent.

Kepler’s ‘eyesight’ is so sensitive, NASA scientists claim that if the telescope were several miles away from a fully lit Empire State Building and just one of its window blinds closed by half an inch, Kepler could detect it.

The telescope’s eye is a scientific instrument called a photometer that continually monitors the brightness of over hundreds of thousands of main sequence stars in a fixed field of view. These data are transmitted to Earth, then analyzed to detect periodic dimming caused by exoplanets or anything else that cross in front of their host star.

The amount of data is staggering, according to NASA’s Kepler website. Equipped with plenty of high-powered, supercomputing power, NASA has been able to analyze all that data.

Major events in exoplanet research and discovery:

The Art of Finding Transit Planets

Thousands of exoplanets have been found so far. Many of them orbit closely to their host sun, so the dip in their light curve is periodic, repeating every few set of days, weeks, or months, depending on the size of the planet’s orbit ring.

From the distance of KIC 8426, a passing planet the size of Jupiter drops the intensity of starlight by 1 percent. Something earth-sized would be a fraction of that.

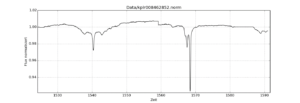

But the transits occurring with star KIC 8462 have astronomers and astrophysicists scratching their heads.

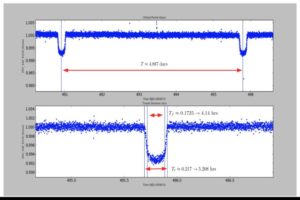

“The Kepler data for the KIC 8462 are pretty bizarre. There are dips in the light, but they aren’t periodic. They can be very deep or very shallow,” said Bovajian. “There’s no rhyme or reason to them.”

Humans verse Computers

When first observed by NASA astronomers, the star wasn’t marked as a ‘having a planet’ candidate by the automatic research pipeline.

Boyajian’s team at Yale wondered about the competency of this pipeline and the computers sifting through the detritus of all that data. What if they missed something, they thought. The human brain has an amazing talent for pattern recognition. What if human eyes could work over the data and find something interesting?

Many in the scientific community scoffed at the idea that human observation could surpass computing speed and precision.

That meant ‘game on’ for Debra Fischer, founder of the citizen scientists group, Planet Hunters, an eager army of 300,000 volunteers who can access Kepler’s data and pour over its findings. “This was the classic humans versus robots challenge that I wanted to win,” said Fischer about joining forces with Boyajian.

Planet Hunters has already found a dozen exoplanets through careful examination of starlight. They would be the same group to clue the professional scientific community in on the KIC-846’s strange goings on.

Seeing something weird is one thing. Figuring out what’s causing the weirdness is a whole different sport, and in this case, it’s a sport nobody knows yet how to play.

TIMELINE – THE HISTORY OF EXOPLANET DISCOVERY AND KIC-846

No Obvious Answers

Count professor Jason Wright of Penn State’s Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics as one of those mystified astronomers working with Bovajian’s team, and leading his own, to learn more.

“While a typical planetary transit will have a very regular shape and a very regular period, the dips in KIC-846’s light curve are highly irregular, both in period and shape,” said Wright. “None of its transits have the characteristic behavior of a planet.”

Jupiter-sized planets dip a star’s light by about 1 percent. KIC-846’s light was dipping more than 22 percent. No planet could get physically big enough to block that much starlight.

The symmetrical and clean u-shaped dipping line from planetary transit is normally constant. There were asymmetrical slopes on either side for KIC-846. Whatever was moving across this star, it wasn’t circular like a planet.

Typical transits last for only a few hours. Light from KIC-846 dimmed for a week.

And then the star was quiet for three years.

Until it wasn’t.

Things That Make You Go: WTF?

Another complex of light curve dips emanated from the star in February, 2013. The dips are of various shapes and sizes and duration. Some dips even have their own ‘up-and-down’ events, a term coined by Boyajian’s team. This lasted for a hundred days—all the way to Kepler’s end.

Boyajian’s discovery paper discusses possible natural origins for the strange signals first acquired back in 2009.

The paper prefaces that whatever is blocking KIC-846’s light is astrophysical. In other words, they claimed, it has to be some thing.

The first theory props up the possibility that the star is very young. That implies the starlight is dimmed by a disk of debris surrounding the star, a kind of swirling soup of rock, dust, ice and gas that eventually solidifies into planets.

Another theory posits that two planets collided in KIC-846’s solar system, and the dimming light occurs because of interfering from that.

Decent theories, but data shows that the star wasn’t a young star, and the glow from super-heated material that would come from a planetary collision was absent.

The paper’s strongest guesstimate proposes a swarm of exocomets passing by the planet, needing to number in the hundreds of thousands, to explain the signal. It’s the theory most consistent with Boyajian’s team’s findings. Still, while a swarm of icy comets could explain some elements of the light curve, there are enough inconsistencies that more observations are needed.

Extraterrestrial Theories Arise

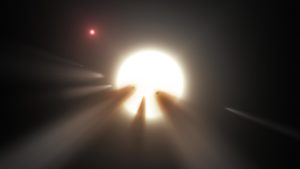

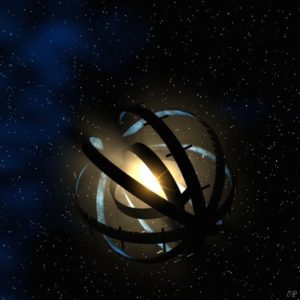

Then another paper co-authored by Wright and other Penn State exoplanet scientists was published. His team proposes the transiting mega-structure theory. In other words, he theorizes that an alien civilization might have constructed massive objects that transit KIC-846.

Wright references the fact that the light curve seen around the star is what someone could expect to see if an advanced civilization were building something. That ‘something’ might be a project along the lines of a ‘Dyson swarm’, in which huge panels get placed around the star to gather solar energy. It could also be a kind of structure beyond our current thinking.

“A transiting megastructure would exhibit a transit shape much different than a spherical planet,” said Wright. “A megastructure that changes its shape on orbital timescales could lead to non-periodic signals. At this point, I just think we can’t conclusively rule it out.”

In his search for the truth, Wright still holds on to one of his core philosophies: that one should reserve the alien hypothesis as a last resort. He says his main reason is analogous to a famous commandment adhered to by most credible exoplanet hunters: Thou shalt not embarrass thyself and thy colleagues by claiming false planets.

Besides, since the light coming from the star is already millions of years old, intelligent design behind KIC-846’s dimming lights might not even be around anymore. Or?

The prospects for finding intelligent life are what gives legs to KIC-846’s popular allure. Stephen Colbert talked to Neil DeGrasse Tyson and Seth MacFarlane about it at length on The Late Show. The Atlantic wrote a feature article about it.

The Search For Funding

And Boyajian has taken advantage, starting a Kickstarter crowd-sourcing campaign to fund observation research for the next several years. As of November, 2016, she’s already garnered over $100,000.

For now, KIC-846 has the funding to be observed for another two years. Now it’s up to the astronomers to figure out what in the universe is happening.

Tabitha Boyajian describes her successful efforts to fund research through Kickstarter: