By Rudi Anna

4/25/2017

Some people will do anything to tweak their behavior.

LINK – HISTORY of PSYCHEDELICS and SOCIETY (storymap by Rudi Anna)

They might adopt a new daily routine. They could pick up yoga, wear a red beret, or sign up for a new therapy program. Maybe that new self comes by taking a medicine currently lazy-rivering on the (legal) market.

But a large body of evidence claims that, try as ye may, a person’s core personality traits, by the age of 30, are hardwired and stable. Air drop a square mile of cognitive restructuring on anybody, and their embedded, enshrined selves stay put. Lock-jawed, like a pit-bull carved out of eternity.

No credible study has ever shown that personality changes in healthy adults were possible even after a scientifically controlled study or experience. In other words, scientists thought, by age 25, people are who they are. Their behavior has crystalized, and there are no take backs.

It turns out this may not be true, and a method that creates access to real behavioral change may be closer than previously thought.

It’s the controlled use of psychedelic drugs — LSD, MDMA (also known as Ecstasy), and psilocybin, the psychoactive compound found in magic mushrooms.

LSD, that 1960s counterculture drug of choice deemed illicit in the United States, continues to make headlines after being repurposed by Silicon Valley tech workers looking to enhance their productivity and creativity.

It was in the news recently after the January release of a memoir, “A Really Good Day: How Microdosing Made a Mega Difference in my Mood, My Marriage, and My Life,” by Ayelet Waldman, who claims microdoses of LSD calmed her down, helped her marriage, and otherwise dramatically improved her life.

Several clinics are conducting trials of MDMA to treat sufferers of post-traumatic stress disorder after conventional therapy has failed. One published in the November 20th issue of the Journal of Psychology showed that 83 percent of PTSD sufferers treated with the drug experienced a significant reduction in symptoms. The principal investigator of the study, Dr. Michael Mithoefer, found that patients can sit for eight hours, talking over their fears and memories with a therapist while the MDMA provides an emotional cushion.

Teams of doctors and psychologists across the globe have presented a new wave of research showing promising evidence that points to the medicinal benefits of these psychedelic substances. In most of the studies subjects receive relatively few doses to mark beneficial treatment progress.

This flies in the face of general common sense on how drugs work. The prevailing idea remains that one dose of something can’t succeed where months of traditional psychotherapy and antidepressants usually fail. It’s foreign to the model.

But high success rates in other ongoing concurrent studies at New York University and Johns Hopkins University strongly suggest that psychedelic-assisted psychological healing is no fluke. The results heavily favor the benefits of these substances, the sample numbers are growing, and multi-site trials are happening internationally.

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), a nonprofit research and educational organization that develops contexts for the careful use of psychedelics and marijuana, reports publishing results at an expanding rate.

“What appears to be going on with the LSD and psilocybin studies is a model system for creating ‘quantum change’,” said Dr. Roland Griffiths, the behavioral biologist who oversees a number of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine studies. “We’ve shown we can safely produce replicable effects.”

This is the quiet, clinical language of a psychedelic renaissance quietly entering its third decade. If its practitioners and advocates avoid the utopian claims and libertarian rhetoric that defined the acid-washed gospel of the 1960s, it occurs as no accident.

A savvy new generation of psychedelic researchers understands that public and official support comes by exorcising the ghost of Timothy Leary, whose democratic LSD crusade grew out of and ultimately worked to destroy the first wave of psychedelic science in the 1950s and 1960s. Their goal is not necessarily to promote the legalization of these drugs or tout their value for everyone but to revive the once-great and now largely forgotten promise of psychedelic science.

A Fresh Start for Old Drugs

This new data, compiled with media attention in recent years about helping cancer patients deal with their fear of death and helping people quit smoking, present a potential boon for the nonmedical, even recreational psychedelic user. As researchers give hallucinogens a renewed look, they’re finding that the substances may improve almost anyone’s mood and quality of life — as long as they’re taken in the right setting, typically a controlled environment.

In fact, it’s something not even drug policy reformers are comfortable asking for yet. “There’s not any political momentum for that right now,” said Megan Farrington, who focuses on hallucinogen research at the Drug Policy Alliance, noting the use of psychedelics is deemed extremely dangerous — on par with drugs like crack cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines.

In 2015, Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley, the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, denounced The Smarter Sentencing Act, a law that arbitrarily cut in half the mandatory minimum sentences imposed on serious drug offenses, noting that it reduced sentencing for LSD, “a drug that causes psychosis and suicide.”

But researchers and experts are taking the idea of drug policy reform for the sake of psychedelic research more seriously. And while the studies are new and ongoing, and a national regulatory model for legal use of hallucinogens is practically nonexistent, the available research appears promising — enough to reconsider the stigmatization and prohibition of these potential wonder drugs.

Hallucinogens’ potentially huge benefit: ego death

The most remarkable potential benefit of psychedelics, also called hallucinogens, is what’s called “ego death,” an experience in which people lose their sense of self-identity and, as a result, are able to detach themselves from worldly concerns like a fear of death, addiction, and anxiety over temporary and traumatic life events.

In most cases, when people take a potent dose of a psychedelic, they tend to experience spiritual, hallucinogenic trips, which make them feel like they’re transcending time and space—even their own bodies. .

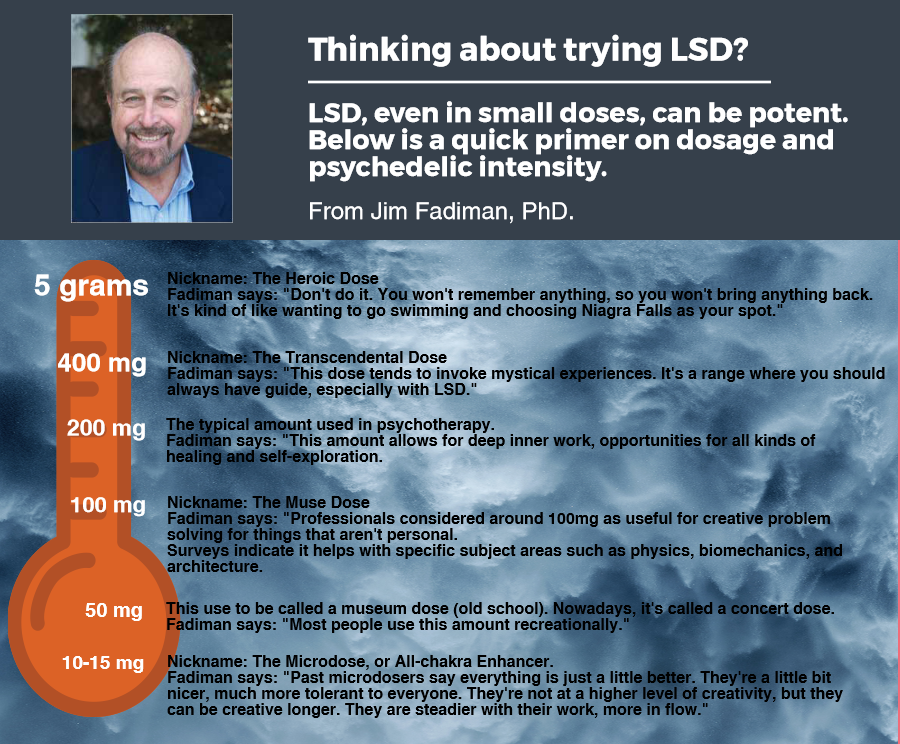

Jim Fadiman, a Stanford University Ph.D. and author of “The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide,” has studied psychedelics since the late 1960s. “This, in turn, gives people a lot of perspective — if they can see themselves as a small part of a much broader universe, it’s a lot easier for them to discard personal, relatively insignificant and inconsequential concerns about their own lives and death.”

In other words, the vivid understanding of connectedness to not only other people but also other things and other systems, becomes a transcendental experience.

“We tend to think that we live separated from everything, or that we’re encapsulated, but our cells turn around every eight years or so, and that material had to come from something,” said Fadiman, speaking with a group of psychobiology researchers at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., about the ego-minimizing effects of psychedelics. “Everything I eat becomes connected to me. Everyone I meet becomes connected to me. That’s all easy to understand and very simple. It’s poetic to say, and all that, but one very important thing you discover is your ego, your personal identity, is not that big a part of you.”

He uses an example of alcoholics he surveyed who had taken a mild dosage of LSD as part of a recovery campaign to kick their addiction. He found that the individuals who claimed to have had a transcendental experience during their LSD session often wound up drinking again a week or so later. At first, he’d think the substance had failed.

But often participants would come back after drinking and say it wasn’t working for them anymore— the drinking was what didn’t work anymore. It reportedly made them feel “less.”

“And what we realized is that many alcoholics are drinking because they feel isolated,” said Fadiman. “They haven’t made this transition into thinking they’re a part of this much larger system. And if we go even further into their background, they may not feel a part of their family and so on. But at the deeper level, if you realize that you’re part of a larger existence, and that’s basically all positive, and if drinking closes that down, why would you do it?”

Fadiman said he believes that for some people, taking a drug allows them to understand that it’s possible to look at the world from a different point of view.

He doesn’t think they’re durable methods that would be healthy for continuous use but considers them indispensable for many people in advertising the possibility in the change of consciousness.

This experience, researchers are indicating, creates an open door, allowing people to change their lives.

“…it helped them regain a sense of purpose, a sense of meaning to their life.”

On first impression, a lot of this may seem like pseudoscience. And the research on LSD and other psychedelics is so new that scientists have said they don’t fully grasp how it works. But it’s a concept that’s been found in some medical trials, and something that many people who’ve tried psychedelics can vouch for experiencing. It’s one of the reasons why preliminary, small studies, funded and managed by organizations like the and MAPS along with research from the 1950s and 1960s found hallucinogens can treat — and maybe cure — addiction, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

In a study at UCLA, Charles Grob, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics who studies psychedelics, gave psilocybin doses to late-stage cancer patients. “The reports I got back from the subjects, from their partners, from their families were very positive — that the experience was of great value, and it helped them regain a sense of purpose, a sense of meaning to their life,” he said. “The quality of their lives notably improved.”

Between 2004 and 2008, Grob administered psilocybin to 12 cancer patients suffering fear, anxiety and depression. His data, published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, showed long-term diminished anxiety and improved mood in every subject.

In 2014, Johns Hopkins University researchers published a pilot study in the Journal of Psychopharmacology that revealed startling success using psilocybin to help heavy smokers quit. Twelve of 15 recidivist smokers who managed to stop smoking for six months after three psychedelic sessions represented an 80 percent success rate—unheard of in the notoriously difficult treatment of tobacco addiction. The most successful current treatment—the drug varenicline, which reduces nicotine cravings—only has a 35 percent success rate.

In an in-depth look at the current research, Michael Pollan at the New Yorker captured the phenomenon through the stories of terminally ill cancer patients who participated in hallucinogen trials:

“Death looms large in the journeys taken by the cancer patients. A woman I’ll call Deborah Ames, a breast-cancer survivor in her sixties (she asked not to be identified), described zipping through space as if in a video game until she arrived at the wall of a crematorium and realized, with a fright, ‘I’ve died and now I’m going to be cremated. The next thing I know, I’m below the ground in this gorgeous forest, deep woods, loamy and brown. There are roots all around me and I’m seeing the trees growing, and I’m part of them. It didn’t feel sad or happy, just natural, contented, peaceful. I wasn’t gone. I was part of the earth.’ Several patients described edging up to the precipice of death and looking over to the other side. Tammy Burgess, given a diagnosis of ovarian cancer at fifty-five, found herself gazing across ‘the great plain of consciousness. It was very serene and beautiful. I felt alone but I could reach out and touch anyone I’d ever known. When my time came, that’s where my life would go once it left me and that was O.K.’”

But Dr. Bertha Madras, a professor of psychobiology at the Harvard Medical School noted that these benefits don’t apply only to terminally ill patients. In studies conducted so far, researchers have found benefits that apply to anyone: a reduced fear of death, greater psychological openness, and increased life satisfaction.

“It’s not required to have a disease to be afraid of dying,” Madras said. “But it’s probably an undesirable condition if you have the alternative available. And there’s now some evidence that these experiences can make the person less afraid to die.”

Madras added, “The obvious application is people who are currently dying with a terminal diagnosis. But being born is a terminal diagnosis. And people’s lives might be better if they live out of the valley of the shadow of death.”

The current research remains in its early stages, a lot of the science still relying on studies from over 60 years ago. But the most recent preliminary findings are promising enough that experts like Madras are cautiously considering how to construct and fine-tune a model that would let people take these potentially beneficial drugs legally — while also acknowledging the enormous risks psychedelics do pose.

The biggest risks of hallucinogens: bad trips and accidents

You would be hard-pressed to find a credible doctor who would say that hallucinogens are perfectly safe, but they’re increasingly being considered by the medical community as less dangerous than people might think.

Rich Doblin at his office in Belmont, Mass. (Photo: Rudi Anna)

Richard Doblin, who has a Ph.D. in public policy from Harvard and is the founder and executive director of MAPS, is helping pave the way in psychedelic research.

Doblin maintained there’s little to no chance that someone will become addicted to psychedelics. He said they’re not physically addictive like heroin or tobacco, and the experiences are so demanding and draining that a great majority of people simply won’t be interested in constantly taking the drugs.

He also said that “hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, which can cause the disturbances widely known as ‘flashbacks,’ is uncommon, but you will see it, particularly among someone who has taken hallucinogens a lot.”

Fadiman drew a comparison to marijuana to explain the risks. “The risk with cannabis is, primarily, that you lose control of your cannabis taking,” he said.

“The risk with LSD is primarily that you’ll do something stupid to ruin the experience, or you’ll have such a scary experience that it’ll leave you damaged. But those are safety risks rather than addiction risks.”

This gets to the two major dangers of psychedelics: accidents and bad trips. The first risk is similar to most scheduled drugs: when people are intoxicated in any way, they’re more prone to doing dumb things. As Fadiman explained, “Some people take LSD and think they can fly and jump off buildings. It’s true that it’s a drug-critic’s fairy tale, but it’s also true in that it happens. Some people drop acid and run out in traffic. People do stupid shit under high doses of psychedelics.”

Bad trips are also a concern. A bad psychedelic experience can result in psychotic episodes, a lost sense of reality, and even long-term psychological trauma in very rare situations, especially among people using other drugs or with a history of mental health issues. Just like psychedelics can lead to long-term psychological benefits, they can lead to long-term psychological pain.

These risks are why not many people are seriously discussing legalizing psychedelics in the same way the U.S. population accepts alcohol or is now beginning to accept marijuana. But leading experts believe there could be a way psychedelics could be legalized in some capacity.

“I think it’s a bad idea to treat hallucinogens like we treat cocaine or cannabis,” Fadiman said. “They pose different risks and offer different benefits.” He added, “But I don’t think we’re ever going to free these substances from careful legal control.”

Hallucinogens: the path to legalization

Researchers believe the best way to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of psychedelic use is to allow people to take them in a controlled setting, in which multiple participants can be observed and cared for by trained supervisors who ensure the experience doesn’t go poorly.

So far, this is what the medical side has focused on. Typical medical trials involve doctors watching over a deathly ill patient or someone dealing with addiction who takes a psychedelic dosage. But if the concept is expanded to allow nonmedical users, then perhaps professionals who aren’t doctors but who are trained in guiding someone through a trip could take the role. “I imagine someone who has training in managing that experience, and a license, liability insurance, and a facility,” Doblin said.

A typical trial works like this: A psychedelic user goes through a preparation period to understand the full ramifications of the experience. Then the user makes an appointment at a facility offering these services. She shows up at this appointment, takes the drug of her choice (or whatever the place provides), and waits for psychoactive chemicals to kick in. As the trip occurs, a supervisor watches over the user, observing, making sure he’s available to guide her through any challenging parts.

In some studies, doctors have also prepared certain activities — a soundtrack or food, for example — that may help set the right mood and setting for someone on psychedelics. Different places will likely experiment with different approaches, including how many people can participate at once and how a room should look.

Teach someone how to fish and they trip for a lifetime

The most convincing idea so far is letting people take psychedelics in a controlled setting.

If pulled off correctly, medical researchers said it would maximize the best possible outcomes and minimize the worst. Supervisors could help prevent accidents, and they could walk people through good and bad trips, letting users relax and get something meaningful out of the experience.

And the same time, researchers say there are risks to the controlled setting. If a supervisor is poorly trained or malicious, it could lead to a horrific trip that could worsen someone’s mental state. Therefore, regulation and licensing will be crucial to getting the idea right.

Bill Richards, a Ph.D. and member of the Johns Hopkins University research team examining the medical benefits of psychedelics, also envisions a potential system in which people can eventually graduate to using the drug solo. “It’s like Red Cross water safety instruction,” he said. “You start out, you’re a rookie. You don’t go into the pool without a trained, certified person to watch you, guide you, and keep you safe. After a while, your teacher gives you a test to certify that you’re safe to be in the water alone. And you might even get certified to become a trainer, so you can guide newbies yourself.”

Ellen Flenniken, a managing director at the Drug Policy Alliance, has argued for lax regulations that could, for example, make psychedelics legal to buy over the counter. “You dramatically dry up the black market, so long as you have people who have to go through some sort of illicit access point. You’re going to continue to have a black market,” Flenniken said. “From a safety standpoint, this means the percent of consumers who get a reliable product from a reliable source would increase.”

“The ironic thing about prohibition is that it makes psychedelics more dangerous, because they are unregulated and buyers never know purity or potency of what they’re getting,” said Doblin. He added that a change in federal policy could correct that problem and provide safe, legal access to treatment to millions who need it. The path forward to bring psychedelics into the legal mainstream is clear, although the time-line is not.

The debate about which model works best will likely go on for some time, especially if different places test different approaches. There’s no doubt it will be tricky to hash out exactly how to legalize and regulate these drugs, as some states are learning with marijuana.

More clinical tests means more data which means more certainty. This is what doctors and advocates are working toward with psychedelic drugs. If it turns out the benefits to public health and well-being are real, it may soon be time for the United States to seriously examine decriminalizing LSD, magic mushrooms, and other psychedelic drugs.